I’m attributing the motivation for this post to public radio, where I heard this recently: http://nonsenseatwork.com/915-when-stubbornness-makes-nonsense-of-persistence/. Persistence is often touted as a key attribute of a successful entrepreneur, and one of the attributes I have remarkable evidence for possessing. But maybe I’m just stubborn?

In an article for HBR, Muriel Maignan Wilkins wrote that you can manage your stubbornness by being open to new ideas and being able to admit you are wrong. The best entrepreneurs I have seen are willing to consider other choices but also balance that with a need to stay on course — changing plans to chase the “next best idea” is not leadership, yet neither is following a course assured to fail. Most adults have likely had an experience where they were convinced something wouldn’t work, and then it did. That’s likely because someone else believed, beyond the obvious reasons why it would fail, that it could work.

In my startup, RideGrid, we believed that people would ride in a car, one time, with an non-professional driver they don’t know. People said we were crazy. You could talk them through the rationale, but safety and trust were their first concerns. That was 2007. Uber has now launched Uber Pool, which has some similar characteristics to RideGrid. Very few people have that safety fear today:

- My mother has used Uber.

- People I work with in Tijuana told me this week that Uber drivers are more trustworthy than taxi drivers — if you left your laptop in a Tijuana Taxi – it’s gone. If you left it in an Uber car, you might get it back.

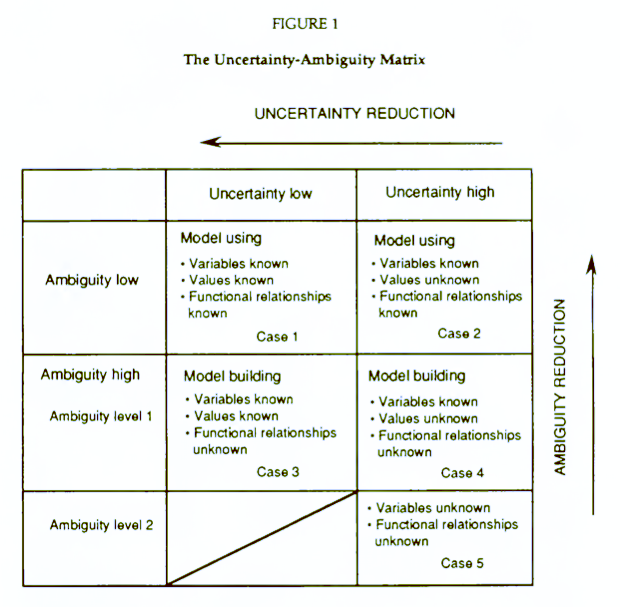

Good entrepreneurs analyze evidence and motivation, and can pivot when they believe they are wrong, but don’t shift at intuition before doing some analysis. Jumping at the intuition of others is entrepreneurial suicide. The analysis doesn’t have to be quantitative, but must consider all relevant variables and their interaction. The entrepreneur also has to filter out distractions of analyzing too much.

Tolerance of ambiguity, self awareness, and the fearless pursuit of what might end up being a waste of time but you don’t think so….. that’s persistence, and there is nothing stubborn about that.

This post is also the subject of a Leadership Minute Video.